.png)

Carneynomics Part 2: Canada's Intangible Opportunity

December 22, 2025

By Laurent Carbonneau

CCI Director of Policy and Research

A few weeks ago I wrote about the 2025 federal budget and “Carneynomics” — the broad economic vision of Prime Minister Mark Carney and his team. In a nutshell, this vision is focused on producing and selling more, and selling it to more markets around the world.

It’s fair to say that my first Carneynomics post was a little bit critical, in that the government is leaning on natural resources and traditional industries, when perhaps we should be doing more to orient Canada towards 21st century value-added industries.

But one area that warrants special focus in Budget 2025 is a commitment to take action on the federal government’s IP policy suite. Finance Minister François-Philippe Champagne’s budget reinvested in IP education programs as well as the Innovation Asset Collective, a patent collective that protects freedom to operate for member companies in cleantech.

Significantly, the government also committed to “an intellectual property performance review to identify new ways to partner with emerging and scaling intellectual property-intensive firms, increase domestic investment in leading and high-potential firms, retain and commercialise intellectual property in Canada, and help firms to protect and commercialise their intellectual property in foreign markets to advance trade diversification.”

The centrality of intangible assets to the modern economy is a trend that is intensifying, not retreating. Serious policymaking has to take seriously the notion that Canada has fallen behind, and we have to make bold moves to empower Canadian innovators to compete successfully in the modern economy.

The federal government should create and endow a sovereign innovation asset bank to do precisely this.

A sovereign innovation asset bank would address weaknesses in Canada’s economic structure that lead firms to undervalue IP early on, and to begin to build infrastructure that can build up innovation strength in key technology areas.

Let’s walk through why it matters and what can be done.

Intangible assets, including IP assets like patents and proprietary datasets, as well as brands and other forms of intangible capital, are now the biggest drivers of company growth and success. The dominance of intangibles creates winner-take-most dynamics within industries, and zooming out, this same dynamic plays out even at the national scale. The growth and success of individual firms has never been more important to overall economic and productivity growth. The American economic boom of the past decade, driven in large part by their tech giants, is just the most visible part of this broader phenomenon.

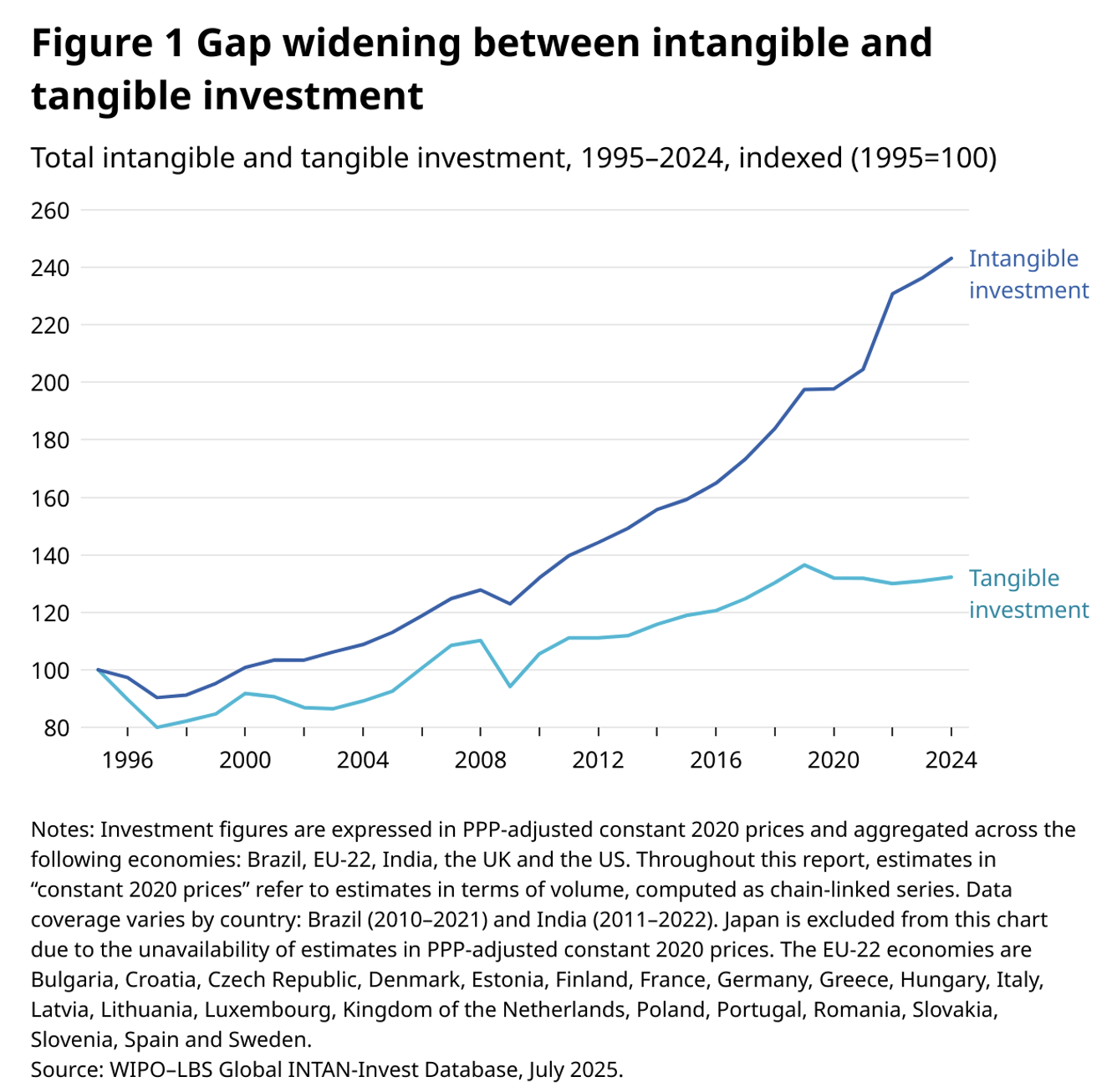

Globally, investment in intangible assets grew three times as fast as investment in tangible assets since 2008, a trend that has only accelerated since 2020.

So what does this mean for Budget 2025? Put simply, now is an opportunity for Canada to course correct.

Companies across different sectors and geographies invest in different intangible assets— patents, data, brands, copyright — for all kinds of reasons that are specific to their businesses. But what those reasons all really boil down to is that companies invest when they expect that the investment to make money.

Canadian policymakers — and much of the private sector — have been watching global markets send a clear signal for nearly a generation now that intangible assets have the biggest potential to create value, and yet Canadians have not done enough to act on that transformation. A useful Statistics Canada paper last year pointed out that sluggish investment in intangibles is a big contributor to our productivity and growth divergence with the United States.

In the United States, having an IP strategy is table stakes for essentially any company right from the beginning, because today’s innovation economy was essentially invented in the US and is reinforced by American-made rules (such as big, multilateral trade agreements).

Best practices from well-run American companies spill outwards. Investors and founders of companies are savvy as to why IP management matters, creating a virtuous cycle — Americans set the rules and learn how best to play within them. And despite the free-market trappings of the American system, the US government has its thumb on the scale for its domestic tech champions in all kinds of ways.

Correctly, the US government sees American companies as critical extensions of state power, influence and prestige in their geopolitical competition with China. They said as much very directly in their recent National Security Strategy.

Canada does not benefit from these same advantages, and small, early-stage companies often treat IP as an afterthought. And by the time they come to realize the importance of intangible assets, it might be too late. The assets you need to guarantee your own freedom to operate might be in someone else’s hands.

Canada has a structural weakness with two distinct elements. Our economy has a lot of small companies that mostly do not have the education and knowledge about IP they need to make smart early investments that can guarantee freedom to operate, and we’re facing strong bases of patents and other assets in other countries that make finding competitive niches challenging. Together, IP education and IP pooling can help overcome these weaknesses.

Smaller economies — Taiwan, South Korea, and Israel, to pick a few examples — have been quite effective in doing this, and were very deliberate in using policy to do it. Korea, for example, has set up sovereign patent funds to help protect Korean freedom to operate.

Canada has already dabbled in education and patent pooling functions at the federal level — this is what the Budget 2025 investments are building on.

But we have an opportunity to get more value out of these programs and allow for truly strategic scale by bringing the education and patent pooling functions under a single roof, as well as management of IP arising from federal research. In-house federal R&D is a roughly $3 billion annual spend, which is pretty significant when you compare that figure to the approximately $4-4.5 billion spent through SR&ED and the federal research granting councils each year.

IP education programming is currently a little scattershot. The Innovation Asset Collective is a useful tool as a patent pool, but too limited in its current mandate (as-is, the IAC can only acquire cleantech patents). And we have nothing in place like the (American) *Bayh-Dole* and *Stevenson-Wydler Acts* that allow for effective and widely-understood rules for commercialization of federal in-house and funded research.

The announced performance review of IP policy should look at all of these elements, and hopefully come to the conclusion that putting these important functions together can help correct Canada’s dangerous underinvestment into intangibles and IP.

JOIN CCI'S NEWSLETTER